This article is reprinted from The Neurosurgical Atlas courtesy of Dr. Aaron Cohen-Gadol a physician member of the Pituitary Network Association. The original article and Dr. Cohen-Gadol’s webinar You Have Been Diagnosed with a Pituitary Tumor, What Next? can be accessed through this link.

What is a pituitary tumor/adenoma?

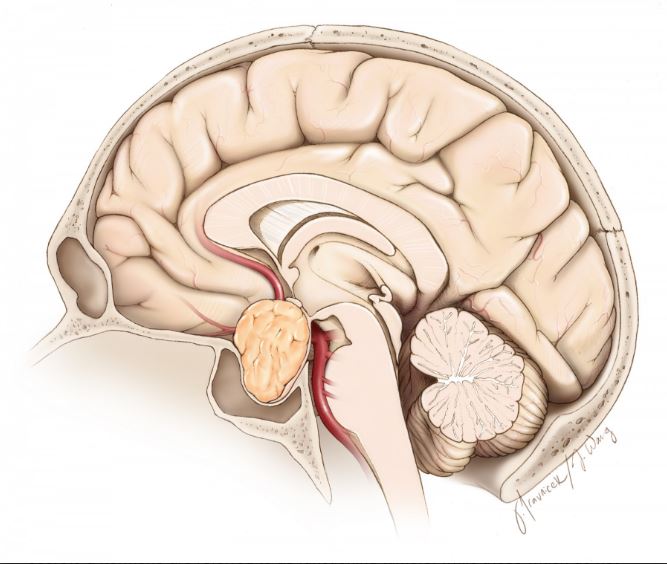

Pituitary tumors are most commonly benign tumors associated with one of the body’s most prominent hormone-secreting structures—the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland is located between your eyes and in the middle of the head at the base of skull. Pituitary tumors are slow-growing, non-cancerous, and will not spread to other parts of the central nervous system or body.

Cross section of a pituitary tumor

Pituitary tumors represent up to one-fourth of all brain tumors. These tumors may or may not secrete a variety of hormones on their own. The pituitary tumors which secrete a hormone are referred to as functioning tumors, while those which do not secrete a hormone are classified as nonfunctioning tumors.

Pituitary tumors are commonly referred to as pituitary adenomas.

What is a pituitary?

The pituitary gland plays an important role in hormonally regulating a wide-variety of body functions, such as growth, metabolism, sexual reproduction, water retention, and the body’s stress response. The stalk-like pituitary is surrounded by major arteries (the carotid arteries), the optic (eye) nerves, and important brain structures like the hypothalamus, which is responsible for regulating many of the body’s homeostatic (stabilizing) regulatory systems (including the pituitary).

Symptoms

The symptoms associated with pituitary tumors are generally a result of altered hormonal function and/or increased local pressure on the optic (eye) nerves caused by the tumor. Symptoms vary widely and depend on whether hormone secretion is altered, what kind of hormone is affected and overproduced, and which structures experience abnormal pressure and compression from the tumor.

Symptoms may be caused by pressure on the surrounding structures like the optic nerves or hypothalamus, or from decreased hormone output from the increased pressure on the pituitary gland itself.

Symptoms include:

- Headache

- Temperature sensitivity

- Excessive perspiration

- Decreased appetite

- Double vision, blurred vision, and/or poor peripheral vision

- Lethargy

- Nausea and vomiting

- Weakness

- Decreased libido

- Menstrual disorders

- Excessive thirst/frequent urination

- High or low blood pressure

- Constipation

- Slow-growth

- Late- or early-onset puberty

The remaining symptoms result from excessive levels of one of the following hormones.

Prolactin, which causes:

- Infertility

- Irregular or absent menstruation

- Decreased libido

- Production of milk and abnormal discharge from the nipples (galactorrhea)

- Osteoporosis

- Impotence

- Vaginal dryness

- Erectile dysfunction

Growth hormone, which causes:

- Enlargement of the hands, feet, face, tongue, and/or other soft tissues

- Gigantism

- Coarsening of facial features

- Sleep apnea

- Facial paralysis on one side

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Joint and bone pain

- Abnormal or excessive perspiration

- Oily skin

- Impotence

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which causes the symptoms of Cushing’s Disease:

- Rapid weight gain, particularly in the torso and face out of proportion to the limbs

- Insulin resistance leading to hyperglycemia and diabetes

- Thin and weakened skin that is prone to bruising

- Striae of the skin (lines/wrinkles/stretch marks)

- Hirsutism (facial and male-pattern hair growth)

- Psychological symptoms such as mood swings, depression, and anxiety

- Weakened muscles and bones

- Backache

- Hypertension

- Decreased fertility in men

Thyroid stimulating hormone, which causes:

- Increased appetite

- Weight loss

- Irregular heartbeat

- Tremors

- Fatigue

- Muscle weakness

- Insomnia

- Abnormally frequent bowel movements

- Swelling in the lower extremities

- Nervousness/irritability

- Decreased fertility

- Excessive sweating

Diagnosis

Pituitary tumors are found in men and women of all ages, although they are more common in older patients. The majority of tumors are not hereditary, although there are certain very rare hereditary conditions—such as multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 1 (MEN-1)—that increase the risk of developing such tumors.

Diagnosis is based on a variety of factors, including clinical history, physical examination and laboratory/radiological findings.

Your doctor will begin by taking a history in order to identify possible symptoms of pituitary disorders and eliminate alternative diagnoses. A physical examination is usually done to identify deficits in vision or changes in appearance that may be attributed to a pituitary tumor (Please see the changes associated with each hormonal imbalance above.)

Depending on what is found, the doctor may order a variety of tests:

Blood and/or urine tests are done to identify excessive or insufficient hormone levels.

An MRI (or less often, a CT) scan is performed to image the presence of a tumor. An MRI uses strong magnetic fields and radio waves to image soft tissues and detect a pituitary tumor.

Venous blood sampling may be used to detect ACTH-secreting tumors difficult to identify on MRI scans. This test is usually ordered when a patient presents with elevated ACTH levels but no tumor is found upon radiological examination. Blood is sampled from the venous drainage on both sides of the pituitary gland to test for abnormal ACTH levels; this can help identify an ACTH-secreting tumor, as well as which side it is located on.

Your doctor may also order a biopsy of the tumor if further identification is necessary; however, with pituitary tumors, other measures generally provide enough information to identify the tumor, and surgery or other treatment options are often pursued without a biopsy.

Treatments

Treatment options vary depending on the tumor type, size, and degree by which the tumor interferes with the surrounding structures. The three treatment options include:

- Medication

- Surgery

- Postoperative Care

- Radiation Therapy

- Medication

A variety of medications can be used to decrease the production of a specific hormone by the tumor or block the effect of that hormone on the body’s tissues. Additional medications may be used to substitute for low hormone production.

Prolactin-secreting tumors (called prolactinomas) usually shrink with medical therapy, negating the need for surgery.

Surgery

Surgery is the primary form of treatment for most pituitary tumors except for prolactin-secreting tumors. The type of surgery used and its chance of success depend on the tumor’s size, location and overall invasiveness.

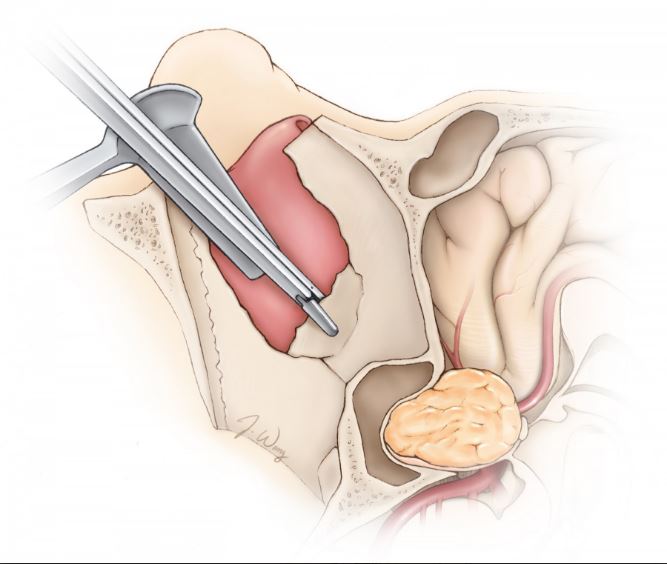

Trans-sphenoidal adenomectomy is a surgical technique utilizing an endoscope to gain entry into the skull through the nose and remove your tumor, eliminating the need for an incision on the outside of the face. This is the preferred method for small, medium, and some of the even large sized tumors. There is no visible scar and no part of the brain is directly touched. This technique therefore minimizes neurological complications.

Endonasal approach to a pituitary tumor

Complication rates are low and most hospital stays are no longer than 1-2 days.

Some of the larger tumors usually cannot be removed in the same way. In such instances, the surgeon may opt for a transcranial adenomectomy. During this procedure, your surgeon exposes the tumor through the upper portion of the skull, through removal of a piece of the skull that will be replaced at the end of the surgery. This is a more invasive form of surgery and post-operative stays are longer—usually between three and four days.

Postoperative Care

The most common procedure is transsphenoidal surgery through the nose which approximately lasts about two hours (Please see video.) After surgery, there is remarkably little discomfort in and around your nose. There is packing in your nose that will be removed approximately 24 hours after surgery. You can usually be discharged from the hospital in 1-2 days after surgery.

During the surgery, the tumor is separated from the rest of the brain by a thin membrane (diaphragm.) If the tumor is large or if the tumor is adherent to this membrane, the membrane may slightly tear during tumor removal. This may cause leakage of brain fluid (cerebrospinal fluid, CSF) after surgery. If this is the case, your hospitalization will be prolonged as your surgeon will plan to repair the leak through placement of a small plastic tube (lumbar drain) in your back to divert the leakage and let the membrane (diaphragm) heal. A second short surgery may be rarely needed to fix the leakage.

During surgery, the back side portion of the pituitary gland may be irritated because of surgical manipulations during tumor removal. This portion of the gland may temporarily halt production of the hormone (ADH) which regulates your urine. Therefore, you may be urinating excessively for days after surgery and you will be given replacement hormone. This situation is usually temporarily and the use of hormone replacement for this purpose is brief.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is most commonly employed after you have had surgery to remove most of the tumor. It there is evidence of growth of the residual tumor after surgery, radiation treatment may be considered. Radiation therapy may come in the form of traditional external-beam radiation or via the more intense and precise stereotactic radiosurgery.

Traditional external-beam radiation therapy directly delivers a single beam of radiation to the tumor. The procedure is usually performed five times a week, for several weeks. The radiation treatments may take several years to bring tumor growth and/or hormone secretion under full control, and the procedure risks damaging normal pituitary function as well as adjacent neural structures.

Stereotactic radiosurgery can deliver higher doses of radiation more accurately by using precise computer imagery and multiple beams to target the tumor. It is does not require any incision and is done as a single-session outpatient procedure. As with external-beam radiation therapy, it may take years for the full benefits to manifest, but unlike external-beam radiation therapy, surrounding structures are less prone to damage from the radiation treatment (although the treatment is usually avoided for tumors near important nerves.)

Radiation therapy may be used rarely as an alternative to surgery in cases where the tumor is inaccessible via traditional routes. Tumor re-growth after surgery may also necessitate radiation treatment.

Prognosis

Most pituitary tumors are benign and slow growing (non-cancerous.) However, the tumors which produce certain hormones may have long-term side-effects that expose you to the risk of heart attack or stroke.

While usually not life-threatening, larger tumors can invade surrounding structures. The removal of these tumors is more challenging and they have higher tendency to recur.

Resources

National Cancer Institute Visit website

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Visit website

Massachusetts General Hospital – Brain Tumor Center Visit website

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Visit website

– See more at: https://www.neurosurgicalatlas.com/patient-resource-center/general-information-for-pituitary-tumors#sthash.legLuGre.dpuf