Which techniques have you developed?

I work mostly in the area of the endoscopic endonasal approach. Specifically, we described techniques to do a stepwise resection of the medial wall of the cavernous sinus. Especially with functional tumors, relatively often, we find the tumor invading or embedded in that membrane. This was developed for Cushing’s disease years ago and was done with a microscope. But we studied it more systematically, and we expanded to other diseases. Our team developed techniques with the endoscope, which allows us to see better, so we can do better resection of the medial wall, and extend it to more pathologies. In addition to the resection of the medial wall, we described different compartments within the cavernous sinus. We described how to navigate within the cavernous sinus and remove the tumor from those areas, which is extremely important. Along with that, we described some unique concepts, like different patterns of medial wall invasion and tumors that can invade ligaments. We described ligaments that were not reported before within the cavernous sinus. These ligaments are important because they anchor the medial wall of the cavernous sinus. You need to disconnect these ligaments to remove the invaded medial wall. And we also study how these ligaments can be invaded by tumors. We continue doing research in these areas, studying better the ligamentous structures and the different compartments of the cavernous sinus. We continue our anatomical research with technical applications. In addition, we follow our patients and report their outcomes, so that we can do this very safely. This is very effective; my remission rates, generally speaking, are among the best you can find in the literature for acromegaly, Cushing’s disease, prolactinomas, even for non-functional adenomas. But at the same time, preserving a similar low rate of complications. So, we can do better without making the patients any worse. And that is why many patients travel to see me.

What is the next frontier in neurosurgery? What do you aim to improve or discover within the next five or 10 years?

Well, there are two routes there: the route of continuing the studies I’m doing, and to keep pushing on the boundaries of the surgical technique. Remission rates and good outcomes are at about 80 to 90%. That means there are still 10 to 20% of patients that have tumors that are too invasive, too difficult, that we cannot fully remove or cure. I think we can push techniques further to make these numbers a bit better, however, there is a limit there. There are some tumors that, even with the best possible technique, will not be curable. Therefore, there is a need for development of newer therapeutics, especially new drugs that can actually treat these tumors effectively. I think that pushing the boundaries of the surgical technique will continue improving patient outcomes. We are also working on highly complex cases, the 10-20% that we cannot fully cure, by doing a type of more hybrid operation. We are able to minimize the amount of tumor with surgery and then use adjuvant therapy, like radiosurgery, CyberKnife in particular, to then treat that residual tumor. And maybe we can help increase the number of patients that are cured or in remission. The preliminary data shows that that we can actually increase by five to ten percent the number of cases that are achieving remission. So, we’re getting closer, with the objective of curing them all.

What inspired you to choose your career path in neurosurgery? And then why did you choose a pituitary specialty?

I chose medicine because of an intellectual interest in how things work in the human body and mind. And I am drawn to the humanistic part of medicine, of being able to actually help people with what you do and have an impact. That is very important, and I got into surgery in particular because that is the most actionable of all medical disciplines. I would say surgery is the one that is the most actionable and where you can physically use your hands to heal people, so I found that very appealing. And neurosurgery, I think, is the highest intellectual and technical challenge because of the complexity of the brain and the skull base. I am interested in the skull base because it is the most intricate area in the head, where we access fascinating anatomy, presenting real challenges. I am always looking for a challenge to motivate myself, and I like to aim toward things that are difficult. The skull base is really, very difficult, because tumors get tangled in blood vessels, in cranial nerves, and are deeply located. These patients often have benign tumors that cause major health issues, which means that the work we are doing can really help and impact their lives. At the same time, if something goes wrong, the impact can be devastating. So, there is a lot to win, but also a lot to lose. Unfortunately, some patients with a malignant tumor will not be cured, no matter how well you do, because of the severity of the disease. But for the most part, these are benign tumors. They may have a very negative impact on the patient’s health, but they are not lethal. Therefore, you always have to temper what you do, and how you do it. It’s very important to be courageous, but you do need to have a very measured courage. You really need to know what you’re doing. What I’m doing seems very risky, but when you are well prepared, you can do very risky things with a very, very low risk profile. This is like when you see someone like Alex Honnold who climbs El Capitan in Yosemite with no ropes. That looks very risky to me, but someone like him has been training all his life to make it look easy. So, we do our best to make complex pituitary surgery look very easy. Even though it appears very risky, we can do it with very low morbidity.

Who have been your mentors?

I had several mentors. Professor Albert Rhoton is the reason why I came to the United States when I finished my training in Spain in 2005. He is widely considered to be the father of microsurgical neuroanatomy. His work has allowed us to do very precise micro-neurosurgery. He was a mentor to generations of neurosurgeons. His work is tremendously influential. Under him, I spent two years at the University of Florida studying in the laboratory, exclusively doing microsurgical neuroanatomy, to prepare myself for a better future surgical career. And believe it or not, that is something that the majority of neurosurgeons do not do as they rarely have spent any meaningful time in the laboratory training themselves. Because you are working within someone’s head, it makes the most sense to spend as much time as possible in the laboratory with human heads to familiarize yourself with it. That was very impactful for me. It allowed me to feel very confident doing surgery, shortening the learning curve because you become familiar with the environment you’re working in. There are many things you can only learn in the operating room, with years of experience, but there are some basic anatomical and technical concepts that you should first acquire in the laboratory, and those are essential to become confident and knowledgeable in the operating room.

When I moved to the University of Pittsburgh, I trained with the pioneering team on endoscopic endonasal surgery. Amin Kassam was the leading figure in the United States and he is my mentor on the endoscopic endonasal approach. He is phenomenally technically talented. He is very innovative, and he was a huge influence on me, along with the whole original Pittsburgh team: Gardner, Prevedello, Carrau, and Snyderman. In addition, I happened to be at the University of Virginia in 2007 when Ed Oldfield was starting his tenure at UVA. He’s regarded as the best pituitary surgeon for Cushing’s disease ever. Although he was not my mentor directly, I had the immense privilege of watching him operate every week for a year and enjoy his masterful operations. That deeply influenced me. He is the one who described how ACTH-secreting tumors can invade the medial wall of the cavernous sinus, demonstrating that it’s important to remove that wall. He’s the one who first did it, and I built a lot of my research and clinical practice upon that knowledge.

Is there anything else you’d like to convey about your work?

My patients know that I’m extremely dedicated to them. They often come to me with the most difficult tumors, sometimes after previous operations that have failed, always with the fear of going through another operation and end up with a complication like a stroke, or problems with the eyes. I’m here for them. I have dedicated my life to this career, to make the best possible outcome for my patients. And I plan on continuing to do my best in the operating room for them. There is no finish line. We continue improving.

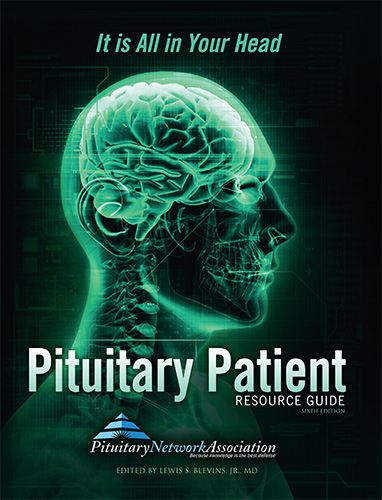

What has been your involvement with PNA over the years?

I’ve been involved for many years, because I think it’s a good resource for patients, and it’s important that they have a place to go and to gather information, to get recommendations, to navigate the difficult process of diagnosis of a new pituitary tumor. And I’ve been doing educational activities, including a number of webinars over the years. The PNA is a great resource for patients. It highlights our work and shares it with the community at large.